Growing levels of resistance and regional variations underscore need for enhanced surveillance, revised guidelines.

By Kalvin Yu, MD, FIDSA, Vice President of U.S. Medical Affairs and Vikas Gupta, Pharm.D., Director of Medical Affairs

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the leading conditions for antimicrobial prescribing in the ambulatory and hospital settings and are most commonly caused by Enterobacterales bacteria, the most common of which is Escherichia coli (E. coli).1 Typically, UTIs are treated with initial empiric antibiotic oral medications. But antibiotic-resistant (ABR) UTIs are becoming more common – particularly among aging populations – and often lead to treatment failures that cause hospitalizations, additional medical visits, and other unintended consequences.

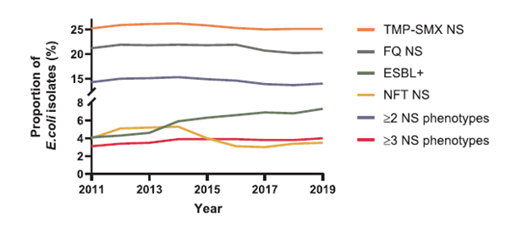

Our data show increases in ABR UTI over the past two decades. We examined outpatient E. coli and Enterobacterales urine isolates for multiple ABR categories, including extended- spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing ABR and bacteria not susceptible (NS) to beta-lactams, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX, Bactrim), fluoroquinolones (FQ, e.g., ciprofloxacin), or nitrofurantoin (NFT). These include the most commonly prescribed oral antibiotics for UTIs: Bactrim, ciprofloxacin, nitrofurantoin and cephalosporins.

We found that ESBL-producing Enterobacterales are increasing in the U.S. These changes, which can be seen in multiple regions across the U.S., can place burdens on patients and the broader health care system. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Threat Report (2019) classifies ESBLs as a serious health threat with an estimated $1.2 billion attributable US health care costs in 2019 alone.

Our data show:

- Between 2011 and 2019, the ESBL+ rate in E. coli increased every year (except 2018), beginning at 4.1 percent and increasing to 7.3 percent. Additionally, Bactrim (TMP-SMX NS) resistant E. coli prevalence was consistently 25 percent or greater and ranged from 25.0 percent (2017) to 26.2 percent (2014).

Source: Antimicrobial Resistance Trends in Urine Escherichia coli Isolates from Adult and Adolescent Females in the United States From 2011 to 2019: Rising ESBL Strains and Impact on Patient Management, 2021

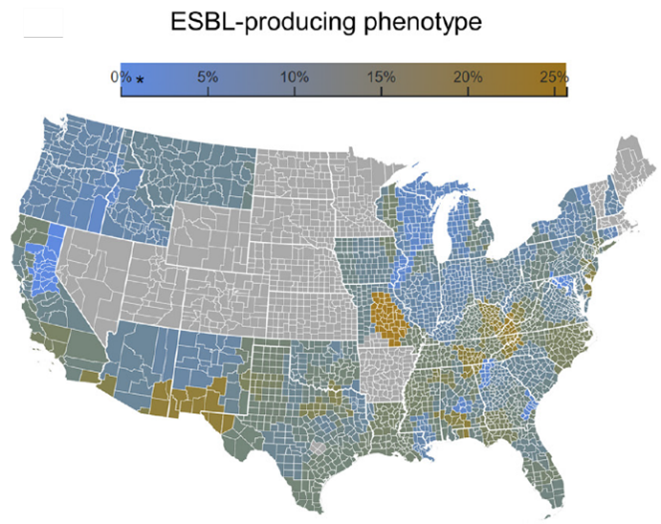

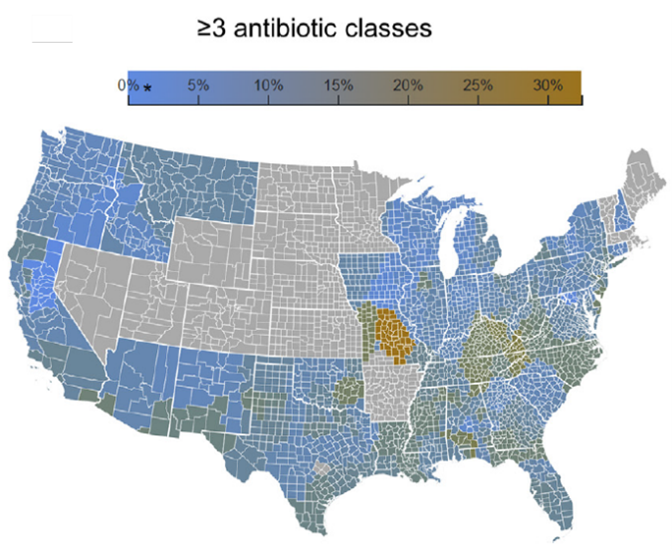

Our data also show significant differences by geographic region across all ABR classes. For example:

- As can be seen in the heatmaps shown below, resistance rates vary not only across U.S. census regions but also at the county level in ambulatory settings, where oral antibiotic options for treating ABR infections are often limited, and even areas with >/= 3 drug resistance – which renders UTIs extremely hard to treat.

- We observed significant differences by geographic region for different Enterobacterales ABR types in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, but most importantly the rates remained above the thresholds recommended for empiric urinary tract infection therapy across most regions. Analyses of geographic distribution by zip code identified subregional and within-state ABR differences for inpatient and ambulatory populations.

|

|

Source: Regional Differences in Antibiotic-resistant Enterobacterales Urine Isolates in the United States: 2018-2020, 2022

An improved understanding of current nationwide resistance patterns can help inform empiric treatment and ABR stewardship efforts in both the hospital and ambulatory setting. Mostly importantly, these resistance patterns support the urgent need to update the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) treatment guidelines for uncomplicated UTIs. As they currently stand, the guidelines recommend that empirical treatment regimens be selected based on expected community resistance rates to avoid the potential for a poor outcome associated with inappropriate therapy. Specifically, Bactrim is recommended for uncomplicated cystitis if resistance rates are <20 percent and FQs are an option for acute pyelonephritis if resistance rates are <10 percent. According to our data, both thresholds to these commonly-used antibiotics are often exceeded across the country, most notably in older patients (e.g., those above 50 years of age).

To mitigate the impact of rising ABR UTIs, health leaders should prioritize:

- Providing timely surveillance on ABR trends at the facility and community level and assistance with analyzing trends to help inform prescribing practitioners.

- Incorporating regional resistance rates into ABR guidelines.

- Given that antibiotic therapy for UTIs is often prescribed without knowing the pathogen or ABR status, diagnosing patients earlier – and with some cursory knowledge of community resistance trends – is important in reducing the overall risk for hospitalization and other unintended consequences.

About BD Infectious Disease Insights

Emerging infectious diseases have been increasing in frequency during the past few decades. None have tested the U.S. health care system’s capacity or resiliency like COVID-19 – forever changing the way that we think about future outbreaks and how we manage the related unintended consequences. The BD Infectious Disease Insights series investigates today’s most prominent infectious disease trends. The series leverages the depth and breadth of our data to serve as an ongoing bellwether on the state of infectious diseases in the U.S., backed by clinical insights on how to increase overall awareness and preparedness.

To subscribe to this series: visit https://news.bd.com/blog.

Subscribe to receive BD blog alerts