By Allison Egger, MPH, CIC

Medical Affairs Clinical Project Specialist at BD & Infection Preventionist at a Baltimore-area hospital

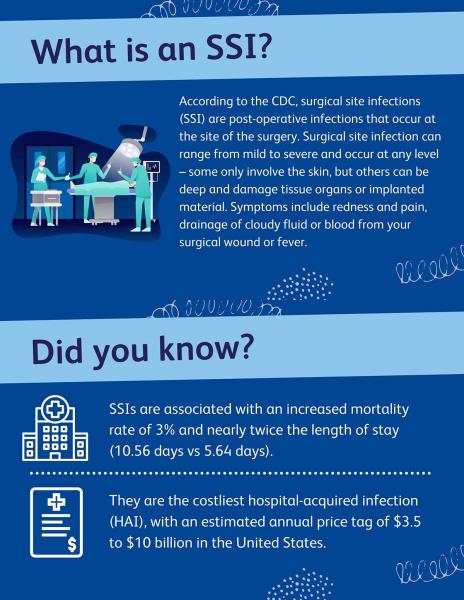

Reducing surgical site infection rates (SSIs) is increasingly important for hospitals and surgical centers alike, which is why the Joint Commission included SSI reduction in their 2020 National Patient Safety Goals.2 When a patient gets an SSI, it can have a devastating clinical, emotional and economic impact on the patient, the surgical team and the institution.3 The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) require hospitals to publicly report their SSI metrics, which are powerful cost drivers and important to patients when choosing where to go for care.4

The good news is that many SSIs are preventable, and as an infection preventionist at a hospital, I’ve seen how the right practices can significantly reduce risk. In addition to appropriate and timely antibiotic choice as well as preoperative warming, studies have shown that rapid PCR screening and decolonization of nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus upon admission can reduce the number of SSIs in a hospital.5,6

The molecular nasal screening and decolonization program that I helped implement for our Orthopedic department has proven to be tremendously beneficial and worthwhile.

Here are 4 key considerations that can help you launch a successful PCR screening program:

1. Do your research

To begin laying the foundation for an effective and persuasive case, gather as much external and internal evidence as possible.

Focus on a department whose leadership and infrastructure can support a nasal screening program. Knowing we had backing from our head of Orthopedics, our literature search started with the orthopedic service line—specifically hip and knee replacement surgeries. To demonstrate the potential “real-world” impact of a new screening program, we analyzed three key data points:

- Internal hospital and local area infection rates: Show baseline prevalence (and thus the likelihood of a patient being colonized with either MRSA or MSSA prior to surgery) by including estimates of the amount of people in a population who may be colonized (have the bacteria in their nasal passages but do not have symptoms) with MRSA or MSSA

- Infected and non-infected cases of your targeted surgeries: Leverage data from your facility’s infection surveillance program. Consider going back about 5 years and include as much detail as is reasonably available.

- Cost data: Help leaders build a strong business case as to how the program could support the organization in reducing the risk of SSIs and their subsequent financial impact to the institution. Our team was able to use facility-specific data through coding and billing to make accurate predictions of potential cost savings. If the facility-level data is not available, standardized metrics can serve as placeholders.

2. Build your plan

After you’ve compiled evidence to support the value of testing in presurgical protocols, prepare your recommendation for a preferred testing methodology, the need for targeted or general testing, and how to implement it. To help target an intervention, research published clinical studies and weigh factors like accuracy, scope of detection, cost and laboratory labor and turnaround times.

Choosing between culture and molecular can be challenging. For our program, the benefits provided by the molecular testing (particularly the ability to detect MSSA, as it has been implicated in SSIs9) and the quicker turnaround time (2 hours10 compared to 24-48 hours11) justified the higher cost of the molecular test.

3. Find your champions

Support from stakeholders who would be integrally involved in the testing process is critical to increasing the likelihood of a program’s adoption. It can increase not only your chances of approval, but also the long-term success of the program. A key partner has decision-making ability within the department and a vested interest in the program’s success, such as a high-volume surgeon, chief of staff or an administrator. For us, the head of Orthopedics in our hospital was an essential advocate for our program. He was able to elevate the issue widely to staff and other leaders who could see that our surgeons felt strongly about investing in SSI prevention.

Share your research and recommendations with those on-the-ground stakeholders who can partner with you to champion your plan. Recruit stakeholders from several different roles, such as physicians, laboratory managers, or perioperative staff. A staff member functioning in a coordination role, such as a clinical coordinator or patient liaison, is particularly helpful, for example, in determining whether infrastructure attached to a specific service line can support additional testing. Leveraging a well-staffed team was a key component to the operational success of our program, enabling us to better anticipate how we could realistically integrate the program into the routine workflow of the preoperative pathway. Not only did this help us ensure the program ran smoothly when launched, but it also was key to its longevity, sustainability, and influence on SSI rates in the long-term.

4. Engage your C-suite

Leverage your initial research to present your C-suite with a strong business case that highlights both patient and cost benefits of reducing SSIs. These include cost data associated with prior and potential SSIs, as well as non-tangible, reputational benefits that may come from lowering SSIs. An important thing to remember is to “be willing to change the status quo” in moving to a new paradigm of preoperative testing.

At my hospital, the Orthopedic program is a high-volume, well-respected program, but was competing with other area hospitals for patients. We had successfully completed SSI prevention strategies like antibiotic standardization and skin decolonization. However, after reviewing the research, our C-Suite agreed that we should implement the nasal decolonization program using molecular testing to help ensure the best patient outcomes.

With the right planning and support, implementing a nasal decolonization program for pre-operative patients could strengthen your infection prevention program and afford similar benefits to patients, clinicians, and your care organization.

For a deeper dive into the data about BD’s molecular testing for MRSA and MSSA, explore our clinical study.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Frequently Asked Questions About Surgical Site Infections. Accessed on September 27, 2021, at https://www.cdc.gov/hai/ssi/faq_ssi.html

- The Joint Commission. 2020 National Patient Safety Goals: Hospitals.

- Perencevich EN, Sands KE, Cosgrove SE, Guadagnoli E, Meara E, Platt R. Health and economic impact of surgical site infections diagnosed after hospital discharge. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(2):196-203. doi:10.3201/eid0902.020232

- CDC. Operational Guidance for Reporting Surgical Site Infection (SSI) Data to CDC’s NHSN for the

Purpose of Fulfilling CMS’s Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program Requirements. Accessed on September 27, 2021, at https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/cms/ssi/Final-ACH-SSI-Guidance.pdf

- Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, et al. American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society: surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 Update. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(1):59–74.

- Bode, L. G. et al (2010). N Engl J Med 362(1): 9-17.

- National Healthcare Safety Network. Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI). Accessed on September 27, 2021, at https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf

- Shepard J, Ward W, Milstone A, et al. Financial impact of surgical site infections on hospitals: the hospital management perspective. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(10):907-914. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2246

- H. Humphreys, K. Becker, P.M. Dohmen, N. Petrosillo, M. Spencer, M. van Rijen, A. Wechsler-Fördös, M. Pujol, A. Dubouix, J. Garau. Staphylococcus aureus and surgical site infections: benefits of screening and decolonization before surgery. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2016; 94(3):295-304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2016.06.011.

- van Belkum A, Rochas O. Laboratory-Based and Point-of-Care Testing for MSSA/MRSA Detection in the Age of Whole Genome Sequencing. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1437. Published 2018 Jun 29. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01437

- Bakthavatchalam YD, Nabarro LE, Veeraraghavan B. Evolving Rapid Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Detection: Cover All the Bases. J Glob Infect Dis. 2017;9(1):18-22. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.199997

Allison Egger is a Clinical Project Specialist at BD. Prior to joining BD in May of 2020, Allison worked as an infection preventionist at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore. She has also worked in infection prevention at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Ochsner Health System in New Orleans. Allison holds an MPH in epidemiology from the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and a BA in Biology and English from the University of Delaware. She has been certified in infection control since 2015. She has presented at several local and national infection prevention meetings and has served on the board of the greater Baltimore APIC chapter for over 3 years.

Subscribe to receive BD blog alerts